The Piece About How We Are “Here, Queer And Speaking Up”

In one of the world’s most homophobic countries, new generation of writers are writing queer people into existence. In a write-up originally published on African Arguments, writer Munachim Amah talks about how LGBT writers are using their ability to tell stories to defy the homophobic status quo of Nigeria.

On Nigeria’s streets, on the pages of its newspapers, and on its screens, members of the LGBTQ community are largely invisible. And with good reason.

Nigeria is one of the least tolerant countries in the world for gay people. In a 2013 global survey, it came out as the most homophobic nation of the 39 polled with 98% of respondents saying society should not accept homosexuality. Another study in 2017 found that 90% of Nigerians support the law that bans gay marriage.

That legislation, passed in 2014, also introduced up to 14-year prison terms for same-sex “amorous relationships” or membership of gay rights groups. Politicians justified it by claiming that homosexuality is “immoral” and “un-African” even though anti-gay laws were first introduced by Western colonial powers.

Since these laws were enacted, there have been some arrests. But members of the LGBTQ community also fear reprisals from their fellow citizens, whether through harassment on the streets or online.

This is why queer people have been erased – or erased themselves – from much of Nigerian society. Being visible brings many risks. But now, a new generation of brave novelists, editors, poets and artists may be changing this. They have been writing queer people into existence, telling their stories and showing that they are humans with bodies, souls, lives and dignity.

A New Generation

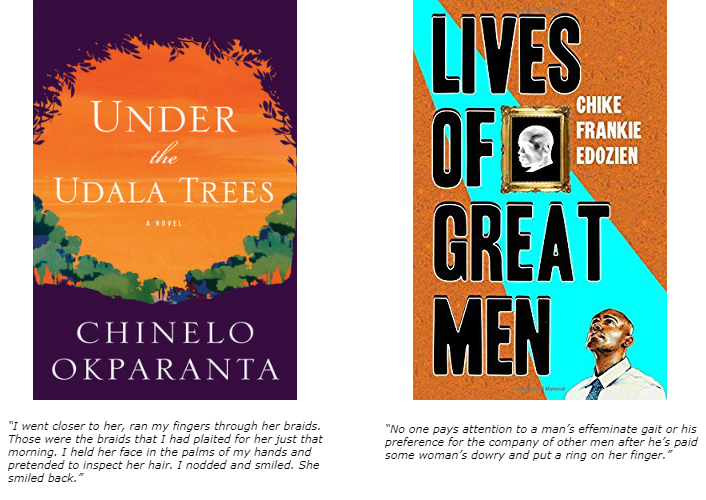

In 2015, just a year after Nigeria’s new repressive legislation came into force, Chinelo Okparanta published her debut novel. A coming-of-age story, Under the Udala Trees is about a young girl who finds herself falling in love with another girl.

Centred on the protagonist Ijeoma, it explores how religion can be used to dehumanise queer people and force them into silence. It is written with a delicate ease, but grapples with tough and traumatic questions as characters are quick to condemn anything they do not understand, often using the Bible to justify their fear.

Under the Udala Trees was described in Bustle as “the most powerful novel of the year”, and it won the Nigerian-born Okparanta a Lambda literary award, a prestigious prize for works on the lives of LGBTQ persons.

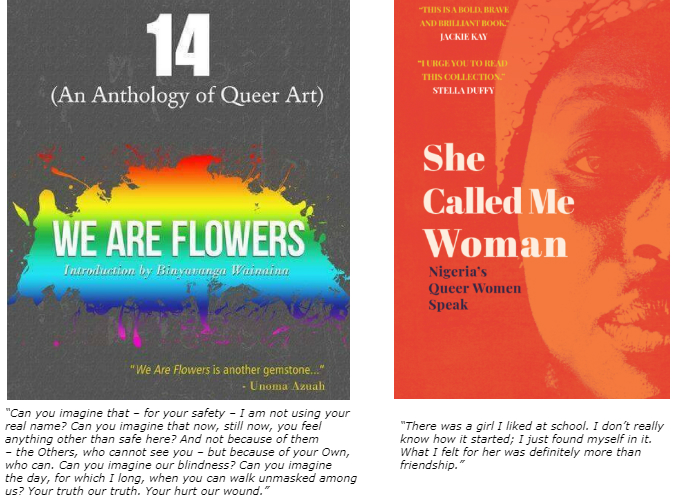

A couple of years later, another brave story of life as a gay person in Nigeria emerged. This one was non-fiction and also penned by an author who was born in Nigeria but moved to the US.

Entitled Lives of Great Men: Living and Loving as an African Gay Man, it follows journalist Chike Frankie Edozien’s travels around Africa and the world as a member of the LGBTQ community. Unlike most Nigerian literature in which non-heterosexual people are either non-existent or hidden away, this memoir is full of gay characters who are bare, alive and very present. Through Edozien’s narrated experiences and reflections, we see a diversity of people as they love, hurt, dream and hope.

Also in 2017, the African literary project Brittle Paper put together 14: An Anthology of Queer Art: We Are Flowers. This project brought together over two dozen young Nigerians who oppose their country’s 14-year sentences for same-sex activity, as referenced in the publication’s title. Through urgent works of fiction, non-fiction, poetry, visual art and photography, this group created a much-needed space for both queer and non-queer people to examine what it means to be LGBTQ.

The collective braved possible retaliation in resisting homophobia so publicly. Later that year, poet Romeo Oriogun was physically attacked and abused online after winning a prize for his “writing on masculinity and desire in the face of LGBT criminalisation and persecution”. A month later, Chibuihe Obi, author of the viral essay, We’re Queer, We’re Here, was kidnapped. Nonetheless, Brittle Paper ran a second volume in 2018 entitled 14: An Anthology of Queer Art | Vol. 2: “The Inward Gaze”.

Earlier this year, the Cassava Republic also published a collection of works by LGBTQ authors. Edited by Rafeeat Aliyu, Chitra Nagarajan and Azeenarh Mohammed, She Called Me Woman brings together stories by 25 queer women across Nigeria.

This ambitious project began in 2015 as the editors travelled the country in search of women willing to tell their untold stories of living in the shadows. In a country where people have been stoned or beaten to death for their sexuality, they often struggled to get people to open up.

“We had people who said they’d do it, but never picked our calls; people who withdrew their stories afterwards, after we’d transcribed and worked on them,” says Nagarajan. “Some of the things they told us, they have never told anybody before.”

Eventually, however, they had enough courageous Nigerian citizens ready to tell their stories to the rest of the country and the world.

No Longer Invisible

These books published over the last few years are neither the first nor the only works in Nigeria to explore queer life. Jude Dibia’s 2005 Walking with Shadows is recognised to be the first Nigerian novel with a gay man as the central character. Meanwhile, there are other publications – such as Blessed Body: Secret Lives of LGBT Nigerians, edited by Unoma Azuah – that are doing crucial work today too.

Together, these collected works have made Nigeria’s literary space ever more enriched with challenging and beautiful stories with queer characters at their heart. These are increasingly being recognised by award-givers as well as audiences. In the past year or so, Oriogun has won the Brunel International African Poetry Prize; Akwaeke Emezi won the Commonwealth Short Story Prize in the Africa category for Who Is Like God; and Arinze Ifeakandu was shortlisted for the Caine Prize for God’s Children Are Little Broken Things.

For generations, queer people in Nigeria have mostly lived in silence and fear. They have been told to shut up and hide to avoid an even worse fate. But now, they are beginning to stand up and speak.

They have always existed – in families, workplaces and on the streets, as well as in literature if perhaps inconspicuously – but despite the risks, more and more queer Nigerians are now telling their stories openly in all their grace and with all their flaws.

1 Comment

Omiete

August 24, 02:20Please how can i get a copy Of the books “lives of great men”and “under the udala trees”